Lebanon

Violent confrontations of the local, sectarian and international actors: “Institutionalized silence” of Lebanon and beyond

Following a long-lasting armed conflict and the tragic persistence of violence and serious human rights violations in its aftermath, Lebanon had to deal with a fragmented, violent and suppressed past. The lack of a structured transitional period, the long-lasting military and political interventions of its bordering neighbors, the continuous political instability and the dramatic tenacity of violence after the civil war constituted a difficult situation. Moreover, the complicated identities of the perpetrators, ranging from domestic military and paramilitary actors of different sects to neighboring states and their local proxies, made the issue of dealing with the past extremely sensitive. The “institutionalized silence”— a notion used by the social scientist Iosif Kovras to describe the Lebanese case—remained intact for several decades.1

Despite various and continuing difficulties and complexities, the situation seemed relatively promising during the post-2005 momentum owing to the relentless struggles of both the families of the disappeared and the domestic non-governmental organizations, as well as the persistence of different international institutions. Novel forms of alliances and new types of activisms, it seems, created an expectant momentum for tackling the question of the disappeared and dealing with the tragic past of Lebanon in the context of the post-2005 momentum. Although this optimistic momentum has changed nowadays, we believe that an assessment of the efforts that made such an expectant atmosphere possible is still relevant.2

Background

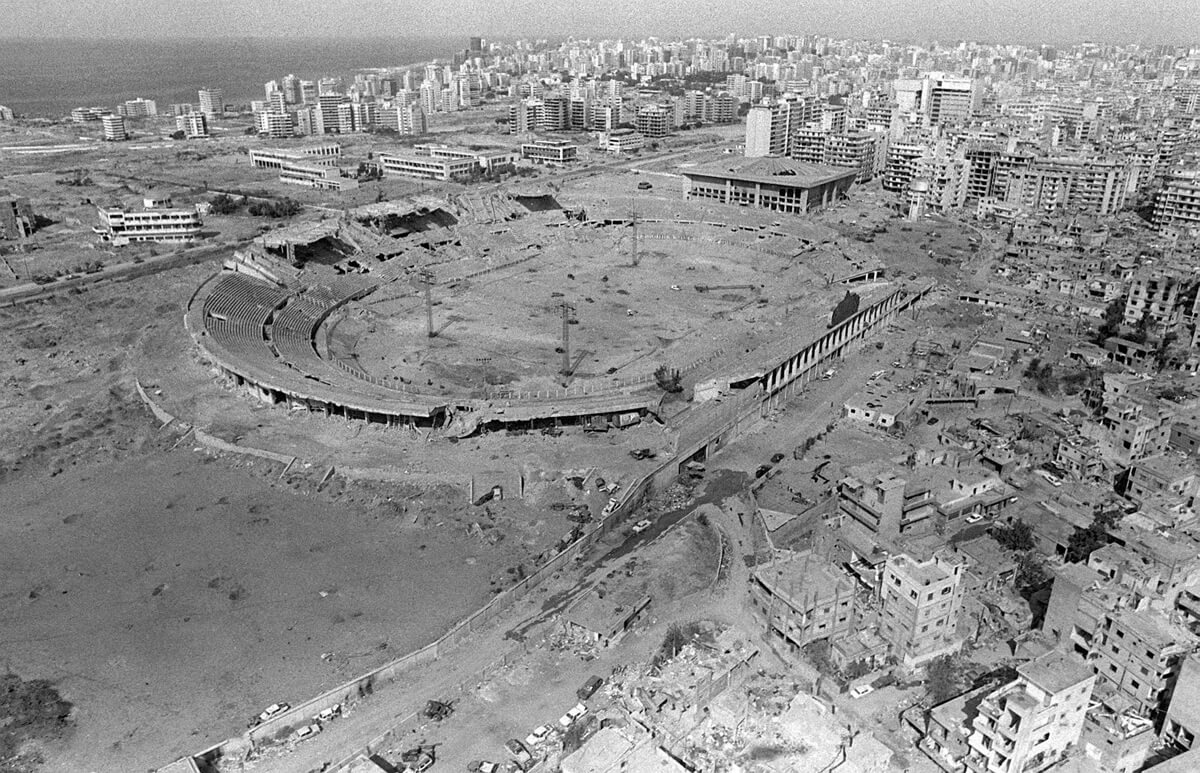

The Lebanese armed conflict, lasting from 1975 to 1990, occurred as a consequence of several conflicts between different religious/sectarian and nationalistic/ethnopolitical identities. Needless to say, different political affiliations also intensified the contentions. Increased political and social tensions between the Christian and Muslim communities of Lebanon were complemented by an escalated internal power struggle among the political leaders of these communities. The long-lasting issue of power-sharing between Christian and Muslim societies was further complicated with the rising influence of Palestinian armed groups.3 The internal violence coupled with the military interventions of Lebanon’s two neighboring countries, namely Israel and Syria; the rising influence of the armed Palestinian groups in Lebanon such as the Palestinian Liberation Organization; the interference of other regional actors such as Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, and finally the interventions of international actors such as France and the United States of America led to the bloodshed of the civil war and its violent aftermath.

During the war, while the radical Christian militants mobilized to protect the political status quo, the oppositional Muslims and members of the political left sympathetic to the struggle of the Palestinians mobilized to change the existing system which was interpreted as unfair to the Muslim community; and hundreds of militant groups engaged in a heated armed conflict.4 Pogroms, massacres, extrajudicial executions, forced displacements, abductions and enforced disappearances were systematically used by all parties as war strategies and resulted in the death of an estimated 144,240 people. The country’s infrastructure and public services were destroyed, the economy completely collapsed and the political system along with its institutions became entirely useless during the war. Approximately 75 percent of the Lebanese citizens reported that they have personally experienced the armed conflict.5 During the first two years of the war, between 1975 and 1977, kidnapping and abductions were widespread, which in most cases resulted in the disappearance of the victims.6

With the intervention of Syria and Israel, both neighbors of Lebanon and both occupying a part of the Lebanese territory, the patterns of the abductions and enforced disappearances changed in the early 1980s. During the war, hundreds of Palestinians and Lebanese Muslims as well as members of the political left in Lebanon disappeared into Israeli detention.7 Moreover, the Syrian factor also complicated the picture: Syria not only directly occupied Lebanon and became one of the major actors of the civil war through its local proxies, but also continued its presence long after the end of the war. During the period of Pax-Syriana,8 “From 1990 until 2005, in tandem with previous forms of disappearances which did not abate, a new pattern emerged; massive waves of abductions of Lebanese were carried out by groups controlled by Hezbollah, with victims transferred to Syrian prisons.”9 The fifteen years of war and its violent aftermath, therefore, created a complicated and complex composite of victims, perpetrators, accomplices and patterns, which affected the Lebanese society deeply by propagating strong feelings of fear, insecurity and loss.

Patterns of Crime

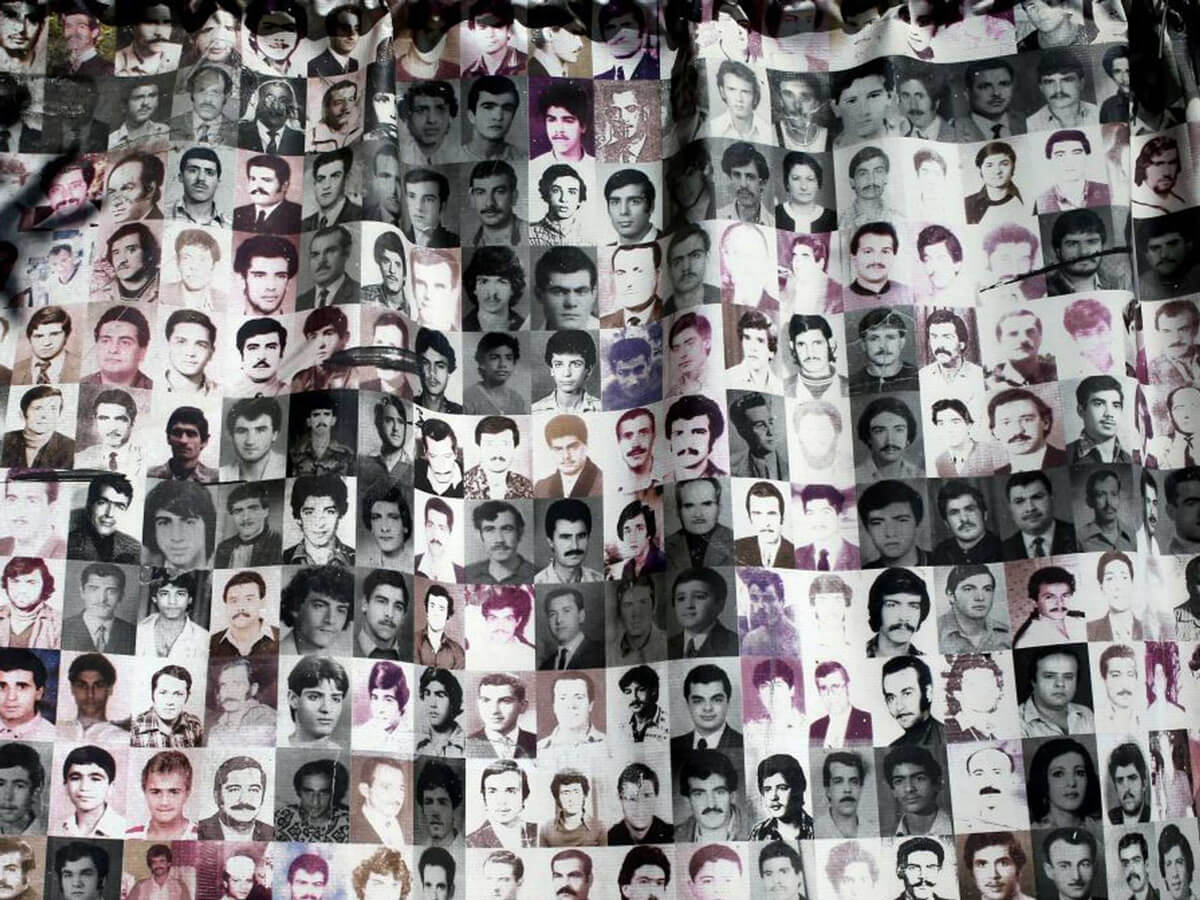

According to a report of the Lebanese government, it is estimated that 17,415 persons were missing or disappeared in Lebanon during the war.10 Lynn Maalouf, a renowned human rights activist in Lebanon, however, finds this number overstated; according to her, the number would be downsized with a thorough documentation effort since this figure is based on the reports of the relatives to the police only, without any investigative follow-up.11 As underlined above, all parties of the war, including the Lebanese army, Lebanese militias, Syrian forces and their local proxies, Israeli forces and their local proxies, were involved in enforced disappearances, which were often perpetrated in coordination between these groups. “Victims—most of whom were civilians—were abducted at checkpoints, as well as taken from their homes or from the streets. They were abducted for a variety of reasons: in exchange for other prisoners; for money or for revenge; and, some observers contend, for the very purpose of creating internal displacement that separated people along sectarian lines.”12

Enforced disappearances did not solely occur in the form of abductions, many individuals were disappeared as a result of mass killings, pogroms and other forms of armed conflict and were buried in mass graves. According to unofficial reports, some of the disappeared were later thrown into the sea. Since there has been no official transition period, or mechanisms of transitional justice, or politics of dealing with the past, there is no accurate data on the profile of the forcibly disappeared, but according to an extensive research conducted by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) based on a 324 family sample, virtually all missing people were men and a majority were young when they disappeared.13 Again, according to the same data, approximately half of the disappeared were married and therefore left behind a wife and often children. Mostly, they were the breadwinners of the family and 72 percent were employed at the time of their disappearances. Last but not least, according to their families, most of them, 82 percent, were civilians and only 16 percent were combatants.

Lynn Maalouf categorizes the forcibly disappeared into three groups:

- Individuals disappeared by Lebanese or Palestinian militias, security agencies, or the Lebanese army (these, however, were also at times affiliated with Israeli or Syrian forces and may have transferred victims to them). Many of these are assumed dead.

- Individuals taken by the Syrian army or its local allies. Many relatives still hold the hope that some of these are still alive in Syrian prisons, and as a result, the victims are often described as “detainees” rather than missing or disappeared.

- Individuals taken by the Israeli army or its now-dismantled ally, the South Lebanon Army. 14

This categorization is crucial for understanding the differentiated demands of the relatives of the disappeared and the different organizations they have founded to disseminate and advocate for these demands. The initial phase of the conflict saw abductions by all armed groups targeting individuals on the basis of religious or national identities in order to instill fear among communities and provoke revenge attacks. In the 1980s, in addition to armed groups, the Syrian, Lebanese and Israeli armies were also arbitrarily detaining and forcibly disappearing individuals, targeting mainly the political and military opponents. Between 1982 and 1983 more than 2,000 individuals are believed to have been abducted by militias or were taken prisoner by the Lebanese army after the Israeli invasion; hundreds were taken prisoner by Israeli forces and transferred to Israel.15 Following the Syrian occupation and domination, the Syrian forces and their local proxies abducted hundreds of individuals, both during and after the civil war. According to Amnesty International, these cases are of a complex nature because such detentions are rarely acknowledged by Lebanese or Syrian authorities and the inquiries made by the relatives of the disappeared to the Lebanese authorities are reportedly met either with denial or indifference.16 In the 2000s, the release of several abducted Lebanese nationals from Syrian prisons after very long periods of time raised the families’ hopes of finding their loved ones alive who were disappeared by the Syrian forces.17

These different patterns of the crime as well as the different actors who perpetrated it created a complicated and fragmented situation in terms of addressing the issue of the disappeared. Thus, as a result of such a fragmented situation, dealing with the legacy of the forcibly disappeared became utterly challenging. The existence of different organizations founded by the relatives of the disappeared with different demands, strategies and methods is yet another result of this complicated picture.

Legal Situation

After the Ta’if Agreement (also known as the National Reconciliation Accord or Document of National Accord) was signed in 1989, which aimed to provide the basis for ending the civil war and returning to political normalcy in Lebanon, important amnesty laws were enacted. However, the return to political normalcy was unfortunately planned to be implemented through an official oblivion and silence. In 1991, a general amnesty law, namely Law 84 was enacted “imposing a blanket amnesty on the prosecution of political crimes, or crimes that have a political aspect, provided they were not committed for personal motive or benefit”.18

The sole exception of this blanket amnesty was the crimes committed against political or religious leaders, which, in a way, created a legal and moral hierarchy among the victims implying that elite victims were more important than ordinary ones.19 Thus, it increased the legal vacuum surrounding the issue of enforced disappearances. However, different authors also argued that this amnesty is not applicable for the perpetrators of the disappearances since the amnesty law exempts the crimes that were committed after the enactment of the law or deemed to be continuous.20 According to this view, enforced disappearances are outside the scope of this amnesty law since they constitute continuous crimes.

The amnesty law, therefore, was a crucial factor among other equally important factors that constructed the scene of oblivion and silence.

Instead of overemphasizing the role of the amnesty law in the context of Lebanon for the institutionalized silence, one should also take into account other factors as well. Iosif Kovras provides a more nuanced analysis for scrutinizing the root causes of the institutionalized silence of Lebanon rather than explaining it solely through the legal lens of the amnesty law, which in fact, reflects the broader multi-dimensional institutionalized silence that was being established. The reasons for this institutionalized silence are: the absence of a minimum level of security due to the ongoing occupation of Israel and Syria as well as the continuing political instability and violence; the lack of democratization of state institutions, especially the juridical apparatus; and the limited presence of international actors for a very long time. Moreover, Kosif also underlines that the embedded security apparatus of militias and landlords remained intact in Lebanon after the Ta’if Accords and even flourished following the “transition”.21 The amnesty law, therefore, was a crucial factor among other equally important factors that constructed the scene of oblivion and silence. Iosif Kovras notes that, since the 1980s only approximately 10 families have brought their cases to the court.22 This dramatic data reveals the structural mistrust vis-à-vis the legal mechanisms that goes beyond the amnesty law.

Another important legal regulation concerning the forcibly disappeared is Law 434 enacted in 1991, which allowed the relatives of the disappeared to legally declare the disappeared relative as deceased if they had been missing for over four years. Although Lebanese politicians presented this law as a solution to the matters of inheritance, marriage, and other civil rights issues, most of the families refused to use this legal remedy since they did not want to declare the disappeared dead without any proof of death or information about their whereabouts.23

Memorialization Efforts

Firstly, three official commissions of inquiry established during the 2000s should be assessed since these commissions, although almost all failed and did not have an impact, reflect the official attempts for dealing with the past and addressing the disappearances. The first post-war commission, composed exclusively of high-level security officials with a timeframe of six months, was established in January 2000 to investigate the fate of the missing and kidnapped. The commission declared that family members had to submit their cases to their local police station, including information about the missing person and the conditions of the disappearance, along with the opinion of the station chief regarding the authenticity of the information. The commission looked at approximately 2,000 cases but it is unclear whether it actually conducted investigations into the individual cases that had been submitted; the details of its work were never revealed.24 Moreover, when, as a result of the strategic litigation process and by the decision of the Constitutional Court the government had to hand over the commission’s files to the families of the disappeared, it became evident that there were no investigations done into the individual cases, merely the forms were collected from the families. In the end, the commission published a short two-and-a-half-page document, which contained no information about the victims, the perpetrators, or the conditions surrounding the disappearances, and presumed all the missing to be dead.25 Considering that five months later, 54 of those presumed dead returned alive from Syrian detention centers, the commission’s legitimacy was extremely poor.

The second commission was established in January 2001 with a mandate of focusing especially on those believed to be in Syrian detention centers. Again, its members were high-level security officials but this time representatives of Beirut and Tripoli Bar Associations were also present in the commission. With two extensions, the commission operated for 18 months and investigated a total of 870 cases. Its final report, initially confidential, was released after the Beirut Bar Association published some important parts of it.26 And finally, soon after the Syrian army’s withdrawal from Lebanon, a third and joint Syrian-Lebanese commission was established in June 2005 with the purpose of disclosing the fate of those gone missing after being detained in Syrian prisons and detention centers. This bilateral commission, also, did not produce any concrete or significant results and apparently, there has been no progress.27

The political pressure, which compelled the Lebanese political nomenklatura to establish these commissions, stems for the most part from the grassroots organizations founded by the relatives of the disappeared. There are three major family organizations in Lebanon: the first one is the Committee of the Families of the Kidnapped and Disappeared in Lebanon (the Committee) established in 1982 with the main demand for the exhumation and identification of the missing who are presumed dead. The second one is the Support of Lebanese in Detention and Exile (SOLIDE) established in 1989 with the main goal of securing the release of the detained/ disappeared from Syrian detention centers/prisons. And the third one is the Follow-up Committee for the Support of the Lebanese Detainees in Israeli Prisons established in 1999 with the main demand for the repatriation of the remains of the missing presumed dead in Israel.28 These organizations with different demands, different positions and sometimes competing solutions, still, managed to establish collaborative relationships after years of communication and dialogue, with the crucial support of local non-governmental organizations such as Act for the Disappeared.

The efforts of these organizations also backed by the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) attained a concrete legal outcome as well. ICTJ commissioned two Lebanese lawyers to draft a report on strategic litigation and “based on this report’s recommendations, the families of the victims of enforced disappearances (represented by SOLIDE and the Committee) filed two motions in May 2009 before the State Consultative Council, seeking to confirm their right to know, and compensation for the state’s non-disclosure of information (based on the 2000 and 2001 commissions of inquiry undisclosed findings).”29 As a result of this effort, on March 4, 2014, the Lebanese State Council, known as Shura Council, ruled for the annulment of a previous decision that denied the families of the disappeared access to documents of the investigations; this ruling also acknowledged for the first time in Lebanese law “the right to know” the truth.30

Moreover, all these continued efforts were influential in paving the way for several public apologies from different sides. First, in 2008, Abbas Zaki, the first Palestinian ambassador to be appointed to Lebanon, issued a formal apology on behalf of the Palestinian Liberation Organization for the harm they had done during their armed presence in Lebanon. Then, the same year, Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea made a similar statement apologizing for the “errors” made during the Lebanese war; however, in this statement he made no acknowledgment of the victims or the violations that had been committed, but rather kept the statement vague and framed his apology as seeking forgiveness from God. And last but not least, the inauguration speech of President Suleiman, again in 2008, represented a change in the official approach of the state as he publicly emphasized his commitment to work hard to release the prisoners and the detainees and also to reveal the fate of the disappeared.31

Lynn Maalouf claims that the post-2005 period, following the end of the Syrian presence in Lebanon and the Israeli occupation that had ended five years earlier, created a new momentum for civil society at large, including the activists and advocates for confronting the past and the issue of enforced disappearances. Kovras, on the other hand, emphasizes the post-2008 period as a time marked by the involvement of international actors. He argues that the support and initiatives of international non-governmental organizations and different institutions such as ICTJ, International Committee of the Red Cross, and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung have been instrumental in analyzing other international examples and different aspects of the struggle of the relatives of the disappeared, and have produced instructive outcomes and reframed the demands in the context of Lebanon.32 The local cooperation among different grassroots organizations despite their contentious positions and the persistent support garnered from international experiences and knowledge seem to establish an example worth examining, despite the loss of the optimistic momentum.

Individual Story

CONSOLIDATED DRAFT LAW

In 2010, ICTJ commissioned a Lebanese lawyer, who also represented the victims of the disappeared, to develop a draft law on enforced disappearances in consultation with a number of pertinent NGOs and families’ organizations33 and with the feedback of international organizations. The draft law proposed to establish a commission to manage the tracing process of the missing, the protection and exhumation process of the mass graves, as well as “other matters related to clarifying the fate of the missing and disappeared in Lebanon”.34 On the background of this draft law, there are immense efforts of cooperation among the organizations of the relatives of the disappeared, as well as strategic thinking on the part of different local NGOs, and international support. Initially, 17 Lebanese human rights organizations gathered and drafted a public memorandum demanding the prioritization of the issue of disappearances, an investigation into the fate of the disappeared based on the official archives, the exhumation of the mass graves, a comprehensive reparation plan for the detained and disappeared and their families, and the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission with the participation of international experts and international non-governmental organizations.35

The drafting of this law has marked an important process of cooperation and collaboration among different stakeholders despite their competing and sometimes contradictory agendas. Even though the positive momentum has changed drastically, it still is an important initiative that also demonstrates both the possibilities and the challenges of collaboration. The lack of cooperation among different stakeholders, which is a global problem that weakens the possible influence of civil society actors, seems to be partially abated with this collaboration. In 2012 and in 2014, consecutively, two draft legislations were submitted to the Lebanese Parliament. The second one, submitted in April 2014, was titled Law for the Missing and Forcibly Disappeared in Lebanon, and was again finalized with the input of the grassroots organizations of the relatives of the disappeared, other local NGOs and international stakeholders such as ICTJ. Unfortunately, neither draft was discussed in the Parliament, however, by April 2015 they had been reviewed and consolidated into a document entitled Consolidated Draft Law. 36 Currently the Consolidated Draft Law is still pending in the Parliament, however, the mere act of drafting it with the input and collaboration of such different and historically contentious stakeholders represents a relative success. Moreover, the contribution of international organizations is also worth mentioning. Finally, it is important to note that this process has led to a number of events, talks, and gatherings which may have an effect on breaking the silence over the issue of enforced disappearances.