Any Hopes for Truth?

A Comparative Analysis of Enforced Disappearances and the Missing in Middle East, North Africa and Caucasus

Özgür Sevgi Göral

Introduction

Navigating through the academic and civil society debates of the last decade, one would feel that enforced disappearance is a phenomenon of the past, and specifically of the 1970s. Despite the fact that it is reappearing in different forms across the globe, enforced disappearances seem to be discussed less and less over the last ten years. Enforced disappearances, described as a phenomenon of the past essentially implemented against political dissidents in South America during the 1970s, are mostly debated in relation to the old dictatorships of the Southern Cone. This perception, however, is sadly misleading; the practice of forcibly disappearing people has produced a variety of patterns, perpetrators as well as political and legal struggles throughout different spaces and times. Moreover, this practice has unfortunately been widespread during the 20th and the 21st centuries in various places across the world. It has been widely used both by the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (OAS – French Special Teams of Counter-Insurgency) against anti-colonial movements during the Algerian Independence War specifically in 1961 and 1962, and by the Algerian government during the civil war in Algeria; by the states and paramilitary organizations in the ex-Yugoslavian countries during the war between 1991 and 2001 when ethnic cleansing, genocide and several other crimes against humanity were committed; in the 1990s in Turkey essentially against the Kurdish dissidents; and during the Chechen War in Russia between 1999 and 2009.1 According to the International Coalition against Enforced Disappearances (ICAED), which is a network of organizations of the families of the disappeared and NGOs, the crime of enforced disappearance continues to be committed today in countries such as Bangladesh, India, Mali, Pakistan, Mexico, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Iran, Sudan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria.2 Moreover, the practices of legal and illegal circuits in the context of the “anti-terrorist war”, such as illegal detentions crystallized in the case of Guantanamo Prison, and extraordinary renditions, which is considered a form of enforced disappearance, prove that enforced disappearance, along with other forms of state violence, has been occurring not only in “underdeveloped countries” but also “in the heart of democracies” such as the United States, United Kingdom and Germany particularly since 2001.3 Hence, enforced disappearance is neither a phenomenon passé nor a practice employed only in eastern and southern dictatorships; it rather manifests as a specific and concrete use of sovereignty by several modern states employed in a global context during different kinds of “states of exception”, if deemed necessary.

This work is a humble attempt to underscore the importance of the phenomenon of enforced disappearance, illustrate its various manifestations, reveal its diverse forms of occurrence in different geographical contexts, and highlight its ongoing consequences. In other words, this work aims to recall the gravity of enforced disappearance with all its complexities in a world where this phenomenon has to some extent been forgotten due to other crucial and immediate human rights concerns and grave human rights violations. Enforced disappearance, as a particular and concrete use of sovereignty by different modern states that encounter different forms of sovereignty crises,4 is continuing to be implemented with different patterns in different contexts. In the contexts where it is no longer practiced, the consequences of this phenomenon, as you may see in the following chapters of this book, still remain very much intact. In this work, I focused on the forcibly disappeared persons of the Middle East, North Africa and the Caucasus. There are several reasons for choosing these regions. This book is drafted as a result of the prior efforts of Truth Justice Memory Center and the Regional Network for Historical Dialogue and Dealing with the Past (RNHDP) to bring together different non-governmental organizations, activists, scholars and grassroots organizations working on enforced disappearances in the Middle East and the Caucasus. As part of these efforts, a workshop was organized in Istanbul on January 27-28, 2017 to discuss the possibility of building regional collaborations among the actors working on disappearances. However, the selection of countries within the MENA region and the Caucasus is not solely based on this workshop either. In this book, I intended to include the most crucial instances that reveal the diversity and different patterns of the phenomenon. While in some cases, the practice of enforced disappearance stems from ethnic or national conflicts, in others the origins of the practice illustrate the structure of different forms of authoritative states. Therefore, all the countries selected represent different dimensions of this phenomenon. Last but not least, in order to provide a more informed and sophisticated picture for each case, I prioritized those cases that we as the Truth Justice Memory Center have been monitoring closely with regular updates from the field.

Throughout this book, two terms that imply different legal categories, missing and enforced disappearance are both used. According to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances, the term enforced disappearance expresses “(…) the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by the concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law.”5 Missing, on the other hand, denotes a broader category that refers to individuals “(…) who are unaccounted for as a result of armed conflict, whether international or internal. They might be military or civilian; anyone whose family has no information on their fate or whereabouts.”6 There are legal distinctions between these two arising from the international human rights law and the international humanitarian law, however, for the purposes of this book, both categories should be included. In some of the cases, such as Lebanon, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Chechnya, both categories are pertinent. Moreover, in some cases, these two terms have been used interchangeably by different stakeholders, including the relatives of the disappeared and the family organizations. And finally, as eloquently put by Iosif Kovras, often these two categories are rendered meaningless in societies affected by this crime. He further adds: “Besides ‘disappearance’ has now become a generic term that is often used quite loosely and tends to include both missing and enforced disappearance.”7

In different contexts, the crime of enforced disappearance is implemented through different patterns. Several aspects are deeply related with the capacity of force and coercion of the state which has implemented the strategy of disappearing. In other words, while dealing with the consequences of the atrocity of enforced disappearance, the power of the state in question is of crucial import; whether it is a strong or a weak state has a significant bearing on the ramifications of this crime. Moreover, the context of the conflict, whether it is an ethnic or ethno-political conflict or is caused by an authoritative state, also influences the actual situation vis-à-vis the enforced disappearances. Whether the conflict is ongoing or has ended and if so the way in which it was ended is yet another important factor determining the status of the disappeared. Finally, the existence or the lack of international actors, including transnational institutions, “foreign patrons,” or different international agencies, shape the legal and memorial status quo in different contexts. In all of these different examples, however, the issue of enforced disappearance and the struggles for dealing with its consequences are closely related with and deeply rooted in the political situation and conjuncture, despite the endless calls for the “depoliticization” of the issue.

Even though there are several differences between the cases, the complacency and undisturbed status of the perpetrators protected by the shield of impunity, along with the ineffectiveness of the local juridical mechanisms are tragically similar. Legal mechanisms of impunity including amnesty laws, deadlocked investigations and futile legal cases as well as intimidation tactics against the families of the disappeared are widespread in all cases. In most of the cases, perpetrators are not only protected by an impenetrable shield of impunity but are also incorporated into the state apparatus, given top ranks in political parties and promoted to important positions in various security and intelligence bodies. This treatment of the perpetrators reveals the key feature of the crime of enforced disappearance: it is inherently and intrinsically linked to the broader state apparatus and modern nation-state structure.

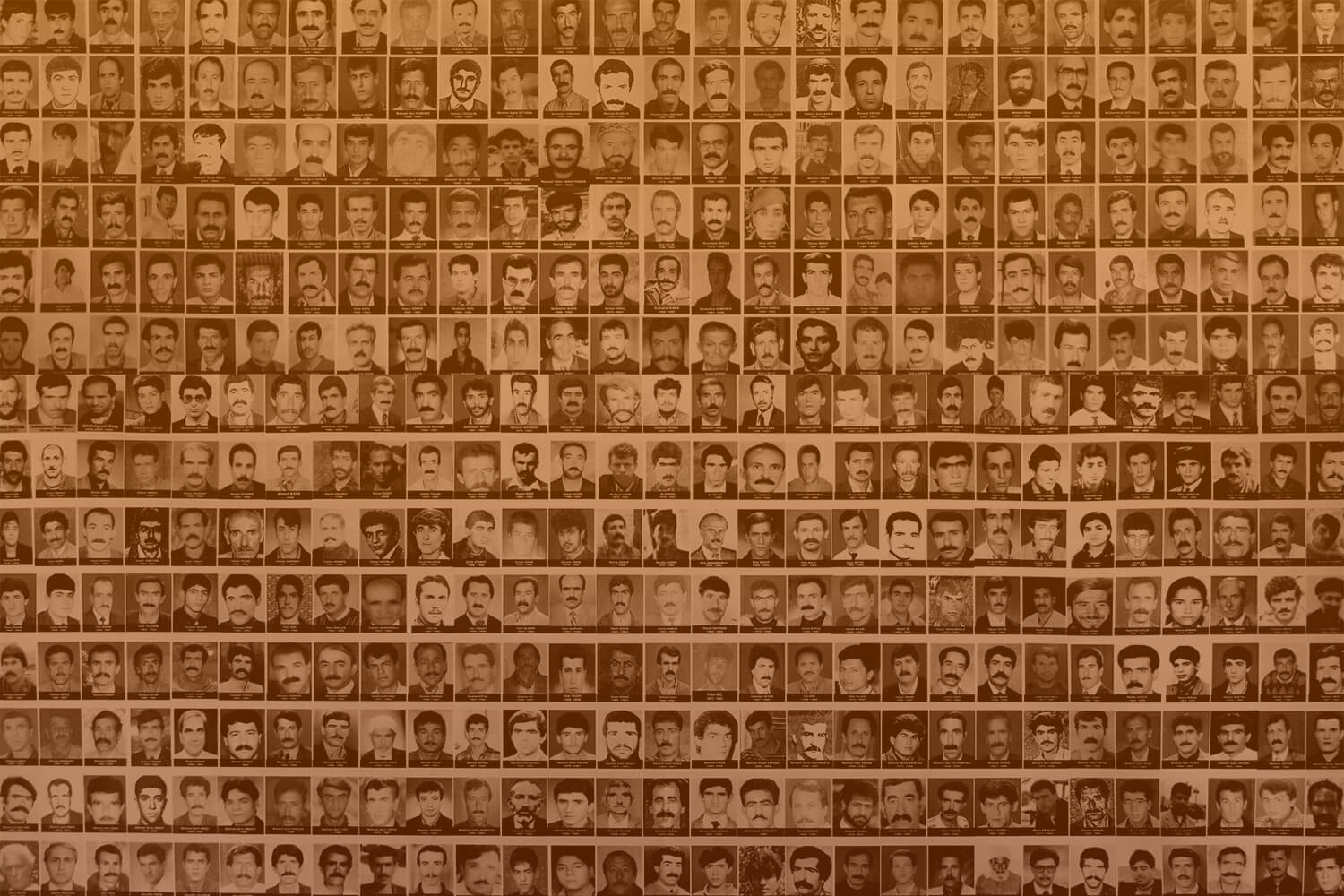

Another striking aspect common to most cases is the predominance of women in the struggle against enforced disappearances. Both the immediate and the long-term period following the disappearance is shaped by and large through the performances, acts and movements of women, the wives and mothers of the disappeared. We know that most of the disappeared are predominantly men although we do not have exact figures for each context. “Inquiries that have conducted gender analyses confirm this pattern, with men comprising between 70 and 94 percent of the disappeared.”8 We also know that the legal struggle after the disappearance, the economic burden of the family, the symbolic role of baring the mourning, and all such material and emotional duties become essentially the tasks of women through a gendered division of labor. Moreover, women’s experiences reveal crucial insights not only into the aftermath of the disappearance but also the patterns of the crime and its specific forms of occurrence. A perspective focusing on the gendered aspects of enforced disappearances has a lot to say in this area as well. “Firstly, such a perspective will reveal that there is never a monolithic experience of state violence and that people with different affiliations experience this process in different forms. Secondly, it will show the need to develop multilayered and customized recommendations to redress the multilayered and multidimensional damages caused by the violations.”9 Nevertheless, studies focusing on the gendered aspects of enforced disappearances, albeit increasing over the last decade, still constitute a very small minority of the literature on the subject. In this work, I tried to highlight the gendered dimension of enforced disappearances while depicting the memorialization efforts and the legal struggles of women in the grassroots organizations and NGOs.

Yet another aspect of the field that focuses on enforced disappearances and struggles against the current of erasure and forgetting, which is extant even in academic and NGO milieus, is its division of labor and partial fragmentation. Put differently, despite the existence of several NGO reports, academic studies, and documents drafted by various activist initiatives, there is still no close cooperation among academic institutions, practitioners and activists. We need more legal, anthropological, ethnographic, theoretical and sociological studies to be conducted on the various aspects of enforced disappearances and in constant dialogue with the relevant documentation and reports of NGOs, activists and grassroots organizations. Such collaboration is crucial for keeping the issue on the agenda of different actors, deepening our knowledge, finding new ways of struggle, and establishing a wider coalition to deal with the crime of disappearance.

Enforced disappearance is a very particular form of state violence where a specific dialectic of seeing and invisibility, knowing and not knowing, surreptitiousness and blatancy coexists. In other words, the implementation of disappearances occurs within a specific dialectic of secrecy and visibility; in one way or another, and even if not in detail, everyone, including the relatives of the disappeared, knows that a catastrophe has occurred. “According to the particular dialectic of secrecy and visibility of the enforced disappearance strategy, the relatives of the forcibly disappeared knew that after being taken into custody their relative was severely tortured under interrogation.”10 However, despite these dialectics, the relatives, comprised mostly of women, have continued to search for their loved ones, knocked on the doors of numerous judicial institutions, and performed different acts of loyalty through a variety of memorialization efforts. They are not only victims, or plaintiffs; they are also political agents. They have survived intimidations, arrests and torture; kept their families together despite tremendous economic hardships; and continued to voice their demands in extremely hostile political environments over and over again. This performativity based on reiteration, albeit with no concrete results in most cases, is itself an act of survival, resilience and hope. One should remember that hope is embodied not solely in a single dramatic act of heroism but rather in the ongoing effort to keep up the resilience and persistence in everyday life. “In this way, hope is not necessarily aimed at the future good, but primarily at the perseverance of a sane life.”11

This work is dedicated to two such actors who continue to encourage, empower and inspire us for “the perseverance of a sane life” under the extremely difficult political conditions of Turkey. One of these actors, Tahir Elçi is now dead, and the other is the Saturday Mothers/Persons. Tahir Elçi was, among other things, the well-known lawyer of the families of the forcibly disappeared; he was one of the builders of the legal struggle against enforced disappearances both at the local and transnational levels, achieving tremendous success in the cases he brought before the national courts and the European Court of Human Rights. As the head of the Diyarbakır Bar Association Tahir Elçi attended a popular television program “Tarafsız Bölge” aired on CNN Turk on October 15, 2015. In this TV program, he stated that he did not define the PKK as a terrorist organization. After this statement, which resulted in the launch of a criminal case against him, Elçi was targeted by several TV channels and newspapers of the mainstream media. On November 28, 2015, he was killed in broad daylight while reading a press statement in front of a historic mosque in the old city of Sur, protesting the ongoing armed conflict in the urban spaces of Diyarbakır. The perpetrators are still unknown; the impunity that he fought against his entire life is now protecting his assassins. The Saturday Mothers/Persons are the relatives of the disappeared and human rights activists who have been fighting ceaselessly for the acknowledgment of the enforced disappearances and the prosecution of the perpetrators. Since 1995, they have been gathering every Saturday in front of the Galatasaray High School, at a well-known and popular square in Beyoğlu, Istanbul, and sitting silently with the photographs of their loved ones who have been forcibly disappeared. Their sit-ins, which were discontinued at times due to police violence and political oppression, were recently declared illegal by the Governorship of Istanbul; however, their legitimacy is very much intact. Their insistence, commitment and resilience are extremely inspiring not only as a civil initiative but also as a persistent political act of belonging, loyalty and hope. This book is dedicated to this kind of hope.