Algeria

Massive Obstacles to Reckoning with the Remnants of les années noirs: Impossible Truth, Justice and Recognition in Algeria

During the Algerian Civil War of the 1990s, a vast number of individuals had been disappeared, one that may only be exceeded by wartime Bosnia. Nevertheless, despite the immensity of the tragedy, it received relatively very little international attention and solidarity. Benjamin Stora, one of the most important historians of Algeria, both of its colonial period and afterward, argued that the public visibility of a conflict made it possible for the victims to produce a coherent narrative. Again, according to him, the Algerian civil war did not have this public visibility and remained mostly in opacity which blocked the emergence of a coherent narrative of the conflict from the perspective of the victims. He accentuated the fact that the Algerian civil war lacked the symbolic and material space of identification and projection. On the one hand, a state of non-law and on the other hand militants struggling for a theocratic Islamic state complicated the emergence of a space of solidarity and struggle. Therefore, according to Stora, the obscurity and blurredness prevailing over the Algerian disappearances is the perfect example of such opacity.1 This chapter may be read as a humble attempt to shed light on this opacity by looking more closely at the disappeared of Algeria, at the undesirable victims in other words.

Background

Enforced disappearance as an official strategy is not a new phenomenon in Algeria, on the contrary, it has historical roots in the colonial past of the country. The French colonization of Algeria commenced after a long, tragic and bloody prelude between 1830 and early 1870s, continued for more than a century and lasted until the end of the Algerian War of Independence in 1962. During the years of French colonization, the strategy of disappearance had been selectively used by the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (OAS – French Special Teams of Counter-Insurgency) against members of anticolonial movements and their various supporters in the context of the Algerian War –specifically during 1961 and 1962. After gaining independence through the struggle led by the Front de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Front – FLN), the Algerian government declared the human loss of the Algerian War as one million.

After independence, the Algerian government followed a statist and authoritative path relying on socialist policies to guarantee work, housing and social services through a statist model. In the early 1980s, however, the government of Chadli Bendjedid commenced a shift toward economic liberalization with severe austerity measures and persisted on its rigid emphasis on a secular state structure, to the detriment of Berber and Islamist identity politics.2 Against this background, civilians began to protest the one-party regime and the ongoing economic crisis with the massive participation of the Algerian youth, first in Algiers and then in other cities of Algeria. Unfortunately, the army repressed this massive mobilization with a massacre of civilians in October 1988 resulting in the death of around 500 and injuring 1000. The period after this massacre, from 1988 until 1991, may be interpreted as the years of rapid erosion of the one-party regime led by the FLN in Algeria.3 In 1989, the FLN passed a number of reforms also allowing for the formation of other political parties. The Front Islamique du Salut (The Islamic Salvation Front – FIS), which advocates an Islamic path for the resolution of the country’s economic, political and cultural problems, emerged from within this context and rapidly mobilizing its supporters won 55% of the votes in the local elections of 1990.

In 1991, the Bendjedid government declared the end of the one-party regime for the upcoming parliamentary elections in which tens of political parties ran and FIS had a tremendous victory: winning “a plurality of votes in the first round [it] was on its way to capturing a majority in the National Popular assembly”4 with the second round of the elections. In January 1992, however, the army organized a coup d’état canceling the second round of the legislative elections, banning and outlawing the FIS, and declaring a state of emergency that would remain in effect for 19 years. The ensuing civil war in Algeria lasted between the years of 1991 and 2002. During these “black years,” les années noires, enforced disappearances implemented by the state apparatus and abductions implemented by the Islamist resurgent groups became one of the main strategies of the civil war violence. Before the cancelation of the elections Islamists had engaged in sporadic acts of violence but in the immediate aftermath of the coup armed attacks became endemic. The state led by the Haut Comité d’État (Supreme Committee of the State – HCE), responded to the violence with a range of repressive and violent practices including massive waves of internal displacement and also “mass arbitrary detention without charge, summary executions, torture of detainees under interrogation, and ‘disappearances’. The practice of ’disappearances’ soared in the mid-1990s, at a time when political violence was at its peak.” 5

Last but not least, enforced disappearances were implemented simultaneously with two other methods: administrative detention and special court trials. After the coup, thousands of FIS militants and elected FIS officials along with members of other Muslim groups were interned in tents in the Sahara, there was also tight surveillance of all the mosques. Although officially closed in late 1995, in these camps more than 9,000 administrative detainees were held in 1992 and several hundred individuals at different times between 1993 and 1995. Also, in 1995, the special courts established for trying “terrorism” cases were closed down. “When these courts were eliminated in 1995 some of the legal provisions governing them were incorporated into Algeria’s legal codes, such as the extension of the maximum length of garde-à-vue detention in ‘terrorism’ and ’subversion’ cases from two to twelve days.”6

Patterns of Crime

During the 1990s, the disappearances were implemented as part of an official policy primarily for intimidating and annihilating the “Islamist terrorist” groups. Although different armed groups such as Groupes Islamiques Armées (Armed Muslim Groups – GIA) and later on Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat – GSPC) abducted hundreds of individuals, it is widely accepted that the army, specifically the gendarmerie and the local “self-defense” groups working in collaboration with the state apparatus and also police officers were the main perpetrators of the enforced disappearances. Moreover, particularly after 1994, when the armed rebellion of different Muslim groups intensified and diversified, members of Département de Renseignements et Sécurité (Department of Information and Security – DRS) also known as the Military Security became more active in carrying out enforced disappearances.7 Among all the various security forces, it was the Military Security that acted with a high degree of self-confidence and also impunity. Moustapha Farouk Ksentini, a human rights commissioner appointed by President Abdulazez Bouteflika in late 2001, told Human Rights Watch (HRW) in an interview that the Military Security is “almost untouchable”.8 Perpetrators primarily targeted individuals who were identified as members or sympathizers of Islamic groups. According to the report of HRW written in 1998, the arrests took place mostly at night and were carried out by a mixed group of security forces: military and police officers, and occasionally members of the local self-defense groups, who arrived in cars with private license plates. According to the testaments of eyewitnesses sometimes armored vehicles were also used. “Some members of these forces wore uniforms and others were in plainclothes. When the police came wearing civilian clothes, they often wore jackets with a recognizable police insignia. When arresting someone at home or on the street, they rarely presented an arrest warrant or official identification. These were reportedly shown more often when the arrest was made at the person’s workplace.”9

In most of the cases, the disappearance of an individual is confirmed by the testimony of an eyewitness. In some cases, especially the ones committed in small towns and villages, the eyewitnesses also confirm that they recognized and could name the individual who took their relative. Although many of the arrests took place at night when the members of security forces could move with ease, relatives had some information about the identity of the perpetrators: in some cases they followed the car and witnessed their entrance to a military facility while in others they noted the features of the automobile and linked it later on to a security unit or the local self-defense groups. In most of the cases, especially when the disappeared was taken during a raid or a security operation and occasionally also when detained at checkpoints, the individual was taken under custody with several other individuals, who later on testified about the disappeared. Also, in a few cases, the families obtained official documents confirming that their relative was in custody. The vast majority of the disappearances occurred in the cities that were mobilized around Islamic political movements and were then hit hardest by the political violence, namely Algiers, Tipaza, Constantine and Blida. “In some cases, the victim’s past political activities or links of kinship, friendship, or acquaintance with suspected militants provide circumstantial evidence.”10

The exact number of the forcibly disappeared is still unknown yet there are some estimations. Based on information provided by the Gendarmerie that acknowledged receiving a total of 7,046 complaints, Human Rights Watch declared that around 7,000 individuals were forcibly disappeared in Algeria between 1992 and 1998.11 An academic work, on the other hand, draws attention to a statement made by human right activists to a newspaper in 2004, which suggests that the total number of the disappeared during the civil war in Algeria may be as high as 18,000.12 The Collective of Families of the Missing in Algeria has collected more than 8,000 testimonies on forced disappearances in the country.13 In any case, the most modest estimation about the numbers of the forcibly disappeared by state and state-sponsored armed forces is approximately 7,000 individuals. If we add this number to the hundreds of detainees abducted by different armed Islamist groups, the immensity of the issue of disappearances in Algeria may be better understood. Although disappearances did not occur systematically after 2002, the situation is still worrying because of the existence and continuation of the secret detention centers.14

Legal Situation

During the civil war years, despite the atmosphere of fear, violence and insecurity, several families tried to use the legal mechanisms for the trial of the perpetrators of enforced disappearances. However, all their attempts have remained futile. In Algeria, not a single member of the security forces or their local allies the self-defense groups have ever been tried. Enforced disappearance does not exist as a crime under the Algerian penal code, therefore, the relatives of the disappeared file their petitions for the offenses of illegal detention and arrest. The Algerian legal framework provides two courses of action for the relatives: “Relatives can either seek to have the state prosecutor’s office in the relevant jurisdiction open a criminal investigation or they can (…) file a complaint before an investigating judge, who examines the facts and makes a recommendation on whether to bring charges.”15 In most of the cases, either the plaintiffs who submitted their petitions to the prosecutor’s office or the investigating judge received no response, or the case remained pending, or the responsible judge closed the file. The legal apparatus, overall, remained useless for the relatives of the disappeared; considering its global scale, the shield of impunity in Algeria was one of the strongest.

Moreover, several amnesty laws had been enacted by different governments. The first amnesty law known as Rahma law was enacted in 1995 with the pretext of rehabilitation of the ex-members of the armed Islamist groups. In 1999, after almost three years of negotiations between the Algerian army and the Islamic Salvation Army, the newly elected president Abdelaziz Bouteflika enacted another amnesty law. Accordingly, all citizens not involved in mass killings, sexual crimes and the bombing of public spaces would be pardoned only for once after deposing their arms. This new amnesty law, enacted after a referendum and named the Civil Harmony Law, theoretically, was designed for the citizens who did not commit serious crimes. However, in practice, very well known warlords benefited from the amnesty and it became discredited from the perspective of the relatives of the disappeared immediately.16 Bouteflika, who claimed to have a disappeared in his own family and used a more balanced language about the disappearances during the initial period of his office, changed his attitude when the relatives of the disappeared reached him to protest the amnesty law. He listened to the relatives of the disappeared who were mostly women and responded: “Forcibly disappeared individuals are not in my pocket. With your photos in your hands and crying, you are embarrassing me in front of the whole world.”17

Moreover, after these three laws of amnesty, impunity grew stronger than ever before and pardoning the bad things that happened in the past became a political and moral order in the country.

The last amnesty law dated 2006 was enacted again by Bouteflika after a three years long campaign which promoted the law as ending the civil war through reconciliation, appeasement and harmony at the societal level. During the campaign, the president emphasized the importance of reconciliation and forgiveness for a peaceful Algeria, however, made barely any mention of how to deal with the atrocities of the civil war period. The new amnesty law, entitled Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation, foresees an indemnification for the families of the disappeared if the disappeared may be declared as dead. Relatives of the disappeared criticized this clause stating that the conditions of the declaration of death are not clear and transparent.18 Moreover, the charter along with presidential decrees for its implementation institutionalizes impunity and impedes any legal action against security services, especially including the DRS, and proposes heavy penalties for anyone who accuses those amnestied of crimes. Besides, one of the presidential decrees has a clause stating that the ones who instrumentalize the pain and tragedy of the civil war for humiliating the Algerian state and its officers will be punished with a prison sentence of three to five years. The charter, thus, not only institutionalizes impunity par excellence but also threatens and targets the civil society and specifically the human rights organizations and their public declarations for dealing with the past.19 Finally, the largest armed Islamist group, Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat – GSPC), has entirely rejected the Charter and any sort of reconciliation based on the charter. The organization, which is known for its ties with Al-Qaeda, also called for the continuation of the armed struggle against the regime. That is one of the reasons why, especially after 2007, suicide bombings became widespread in Algeria again. Moreover, after these three laws of amnesty, impunity grew stronger than ever before and pardoning the bad things that happened in the past became a political and moral order in the country. Such an order, in turn, obscures and once again renders invisible the existence of state violence and the state’s criminal officers. A statement made by Farouk Ksentini, the human rights commissioner and head of the National Consultative Commission for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights established in 2001, reveals this situation most remarkably. In one of his addresses in 2006, he declared that the state might be “responsible but not guilty” for the enforced disappearances.20

Last but not least, there are several mass graves in Algeria. However, so far not much has been done on this issue. Even though several daily newspapers reported the discovery of mass graves in different cities of Algeria, the official institutions have remained silent, neither confirming nor commenting on the existence or discovery of these mass graves. Furthermore, Algerian authorities have failed to disclose their procedures for preserving evidence and identifying the human remains found at these sites. Several international human rights organizations and bodies such as WGEID have asked questions about these mass graves, however, the Algerian government has yet to make any comment on the issue. Human Rights Watch reports that in May 2000 it has been informed by the Algerian authorities that DNA analysis, one of the key tools for identification of the disappeared, was not in use in Algeria.21

Memorialization Efforts

Memorialization efforts in Algeria and the public debate about the official recognition of the disappearances reveal the subtleties of and insights into the Algerian context. On one hand, individuals who were either part of or sympathizers of the Islamist movements made up the majority of the disappeared. On the other hand, their families, the Muslim women who represent these undesirable victims were the publicly visible figures concerning the issue of disappearances. Moreover, the ones abducted by the Islamist groups also had competing political positions, however, the families of the disappeared and the abducted had a number of crucial demands that were common to all. In other words, the representation of the families, as well as the internal relations of different victim groups, were deeply affected by their affiliation with Islamist movements, both at the national and global scale. The international prestige and image of the Algerian state remained relatively intact during the initial years of the 1990s as a state “fighting against Islamist terrorists”.

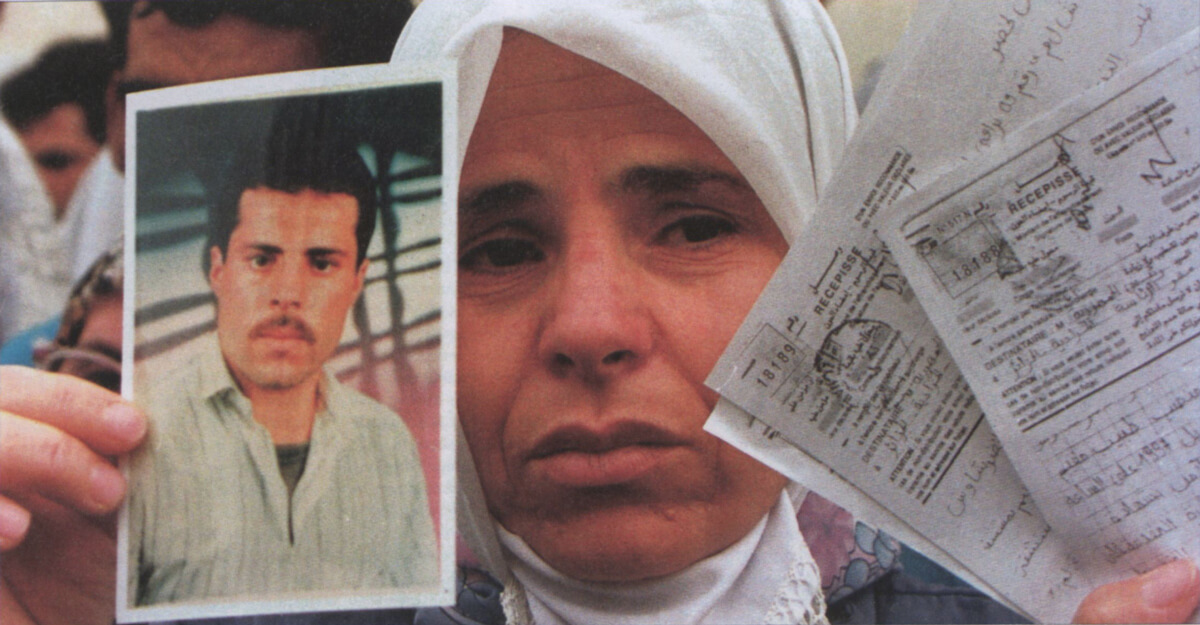

Several grassroots organizations of the relatives of the disappeared emerged in Algeria during the 1970s. In line with the global pattern, the first visible activists were women, the wives and mothers of the disappeared who began to gather together in the autumn of 1997 after the massive waves of disappearances between 1994 and 1996.

During the first timid gatherings the main demand was the trial of the perpetrators, however, as time went by broader demands for truth and memory also began to be expressed by these women. In November 1997, l’Association Nationale des Familles des Disparus (National Association of the Families of the Disappeared) published an open letter to the General Mohamed Lamari, the then chief of state, expressing publicly their demand for justice, truth and recognition.22 Also, during and after the Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan’s visit to Algeria, families of the disappeared staged weekly sit-ins in Algiers, outside the headquarters of the National Human Rights Observatory (Observatoire Nationale des Droits de l’Homme – ONDH), demanding information about the whereabouts of their loved ones. There were frequent demonstrations held also in Constantine and Relizane.23 ONDH was an organization established in the immediate aftermath of the coup d’état in 1992 to address human rights violations in Algeria, however, it always remained ineffective and inoperative on the issue of disappearances except for sending short and uniform letters to the relatives of the disappeared who asked for its help, mostly stating that there is no information available or that the individual had been abducted by terrorist groups. Despite these ultimately discouraging conditions, important grassroots organizations of the relatives such as Somud, Association of the Families of the Disappeared of Constantine, The National Association of Families of the Disappeared and SOS Disparus were able to initiate gatherings, make statements and organize public events even though they did not have legal recognition. Their legal status remained unclear for many years as they did not receive an official response to their requests to acquire legal entity status and be recognized as associations. Besides, they were severely targeted during their peaceful demonstrations, sit-ins and other public appearances depending on the political tensions of the existing regime.

Despite its cautious tone and refusal to provide a list of the disappeared, ONDH acknowledged the issue of disappearances for the first time in 1994 stating that they were receiving hundreds of letters from the relatives of the disappeared. Then, in 1999, the newly elected president of Algeria, Abdelaziz Bouteflika began giving speeches and interviews that signified an important shift in the official discourse on disappearances. First, he admitted that the disappearances represented a huge problem for the Algerian society, uttered the number of 10,000 as the number of people who had been disappeared, and added that the state should investigate these disappearances very meticulously. Secondly, he said that there is a disappeared person in his own family too, thus publicly declaring himself a relative of the disappeared. And finally, he acknowledged that some of the disappeared might be dead, which marked the first time an official openly acknowledged this.24 Also, the government set up offices in cities and districts to receive the complaints about the disappearances. Two factors seemed to oblige the initiation of this discursive and political change: The will of the government to end the civil war and its predominant violence through a sort of reconciliation without a full-fledged democratization was an important factor. And the second factor was the political pressure of international bodies such as the European Union, international human rights bodies, the United Nations and other institutions directed at the newly elected Algerian president to handle the issue of disappearances. Although the steps taken thus far are important they should not be overemphasized. The Algerian case does not represent an example of transitional justice, but rather a series of small steps followed by major backlashes and the restoration of the status quo on the issue of enforced disappearances. Bouteflika was also an ardent supporter of forgiveness and amnesty for the enforced disappearances and thus institutionalized impunity of state officials in a meticulous manner. Moreover, despite his speeches that emphasized the tragedy of the disappearances he did not take any concrete steps for discussing the legal and political responsibility of the official institutions, he rather blocked this discussion with different presidential decrees criminalizing the debates of responsibility, accountability and impunity.

In spite of these circumstances, different relatives’ organizations, namely both the ones that represent mostly the families of the Muslim individuals disappeared by the state and the ones that represent the families of the individuals abducted by Islamist groups were able to cooperate. Collectif des Familles des Disparus en Algérie (Collective of the Families of the Disappeared in Algeria – CFDA) organized an international meeting in 2007 against amnesties, impunity and “imposed reconciliation” with the demand of establishing a truth commission “with the participation of the organizations of state officers’ victims and victims of terrorism”.25 Different organizations representing different forms of disappearances and having contradictory and even competing political positions were able to act together. It seems that the continuation of these efforts is the only means through which a space can be created for a genuine debate on transitional justice.

Individual Story

DISAPPEARANCE OF SALAH SAKER

Salah Saker, a high school mathematics teacher and father of six, was one of the FIS candidates from Constantine in the elections of 1991.26 In December 1991, as a parliamentarian candidate, he won 44 percent of the votes and would probably be in the Algerian parliament if the elections were not canceled. He was one of the hosts of the FIS leaders when they visited Constantine. There are three official versions about the fate of Salah Saker who was arrested at his home on May 29, 1994. Three years after his arrest, his wife Louisa Bousroual, who had filed a complaint with the Constantine prosecutor’s office and made other formal inquiries, received her first official response from the authorities. “It was a police report, dated February 26, 1997, stating that the judicial police of the wilaya of Constantine had arrested Salah Saker before turning him over on July 3, 1994, to the Territorial Center for Investigations of the Fifth Military Region, also known as the Bellevue military center in Constantine.”27 Even though it was thus confirmed that he was handed over to the military, the family’s formal complaint produced no results. Since the family had “also filed a case in a Constantine court asking for the prosecution of the those responsible for Saker’s abduction,” the investigating judge summoned Saker’s wife to discuss the case on March 20, 1999, but nothing has been heard from the court ever since.

The second version of his fate came with a letter from the ONDH dated December 10, 1998, which was sent as a reply to the family’s complaint dated September 27, 1996. In the letter, ONDH stated that based on the information provided by the security services, it appears that an unidentified armed group abducted Salah Saker. The third version came directly from the government in response to Saker’s wife’s petition submitted to the U.N. Human Rights Committee. In the government’s letter to the U.N. Human Rights Committee, it is stated that Saker was:

“arrested in June 1994 by the judicial police of the wilaya of Constantine, who suspected him of being part of a terrorist group that had committed several attacks in the region. After questioning him, and having been unable to establish proof that Salah Saker belonged to the terrorist group being sought, the judicial police decided to release him from garde à vue and to transfer him to the military services of the judicial police, to continue the investigation. After a day-long inquiry, Salah Saker was freed by the military services of the judicial police. He is being sought by virtue of an arrest warrant issued against him by the investigating judge of Constantine, as part of a case involving twenty-three persons, including the aforementioned, all of whom belong to a major terrorist network. This arrest warrant is still in effect because Salah Saker remains at large. He was tried in absentia, along with his co-defendants, on July 29, 1995, by the Criminal Court of Constantine.”

None of the communications received by the Saker family tried to reconcile these official accounts concerning his whereabouts.28